The Quahog as Weather Forecaster: Inside the Research of WWU’s Nina Whitney

Across the world, ocean temperatures are rising.

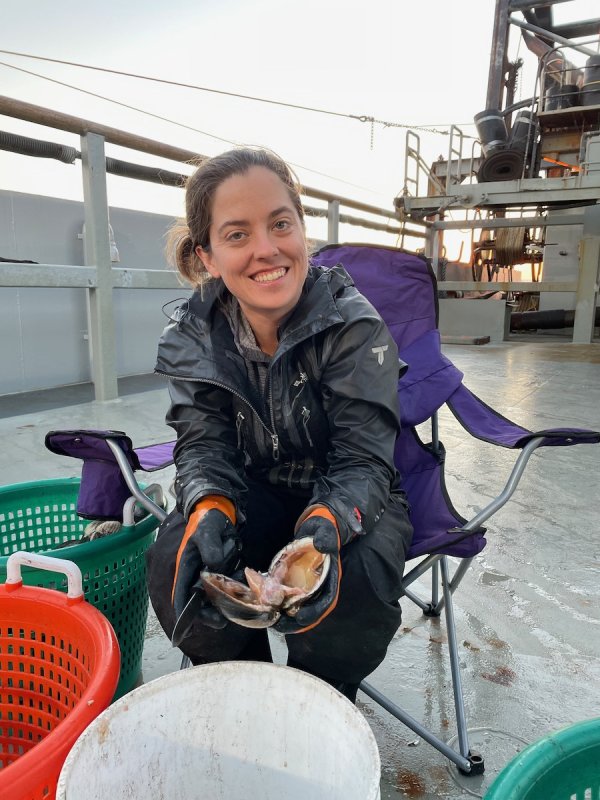

WWU Research Assistant Professor of Marine and Coastal Sciences Nina Whitney has enlisted an unlikely ally in the effort to better understand how quickly these oceans are changing: the ocean quahog (pronounced kow-haag), an East Coast distant relative of the Pacific Northwest’s geoduck clam.

Ocean quahogs have a long story to tell; they hold the record for longest-lived, non-colonial species on the planet, with life spans that can eclipse 500 years – and getting them to divulge their secrets can unleash a trove of data.

“These clams are what we call an ‘environmental proxy,’” said Whitney. “Quahogs precipitate a layer of shell each year the same way a tree grows a ring, and we can pull data from each ring. And when you see how long each of them can live, that is a lot of environmental data hidden in the shell of one clam.”

Pulling that data uses a scientific technique called sclerochronology, the study of physical and chemical variations in the accretionary hard tissues of organisms, and the context in which they formed.

“Sclerochronology allows us to reconstruct changes in the environment that each of the clams experienced while it was alive,” Whitney said. “And using shells from collections we can piece together a pretty good record.”

Whitney has been working with quahogs on this project for more than nine years, from her time as a master’s student through getting her doctorate and then working as a postdoctoral researcher at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution on Cape Cod. A native Mainer who grew up on the coast, trying to better understand the changes that the Gulf of Maine is going through was a natural fit for her research interests.

I just thought it was fascinating, that we could use information hidden in a clamshell to tell us all about the ocean currents, ocean circulation changes, water temperature and more, all from the isotope chemistry and radiocarbon signatures that each clam has.

Nina Whitney

“I just thought it was fascinating, that we could use information hidden in a clamshell to tell us all about the ocean currents, ocean circulation changes, water temperature and more, all from the isotope chemistry and radiocarbon signatures that each clam has,” she said. “And the waters off Maine were a perfect subject, because so many people in my home state rely on that water for their livelihoods.”

Whitney said the goal of her research, which was published last August in the scientific journal “Communications Earth and Environment",” showed that warming in the Gulf of Maine in the 20th century reversed in 100 years the long-term cooling that has been occurring over the previous 1,000 years.

“Yeah, it didn’t take nearly as long to heat up as it did to cool down,” Whitney said. “The warming trends corresponded with a change in ocean circulation that also brought more water from the warm Gulf Stream into the Gulf of Maine, and less from the colder Labrador Current.”

And what do climate models point to as the cause for the changes in ocean circulation and temperature in this region? While everything from volcanoes to solar activity have some input, she said, the main culprit is a familiar one: greenhouse gases.

And while Whitney is certainly keeping busy with both finishing up her current research as well as serving as the Student Engagement lead in WWU’s MACS program (she just celebrated her first anniversary at Western), we had to ask: now that she’s a Pacific Northwesterner, might there be some geoduck research in her near future?

“We’ll have to see,” she said with a laugh. “Not all clams can tell the same story.”

Find out more about Western’s Marine and Coastal Science program at https://marine.wwu.edu/.