From the bottom of the ocean to Washington, DC

Mitchell Hebner (he/him), a master’s student in biology, is taking his passion for marine science and ocean exploration to entirely new realms: federal marine policy.

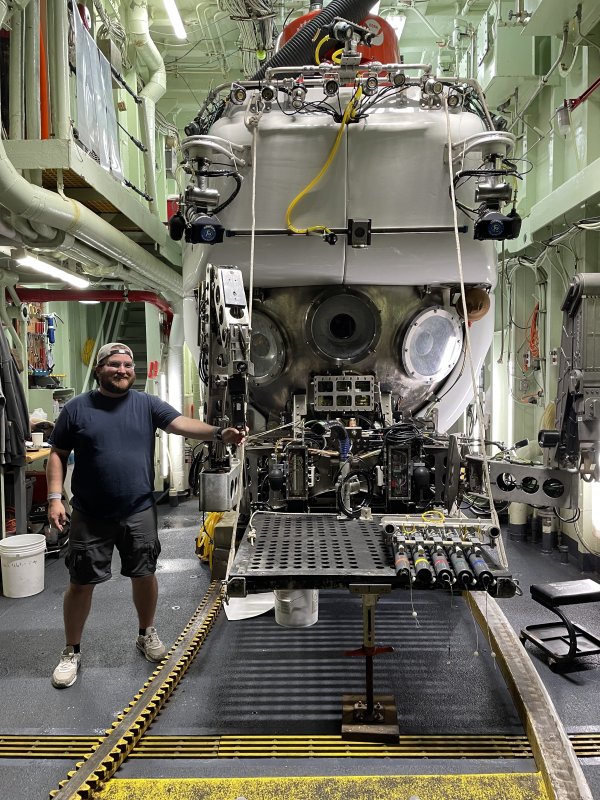

Over the past several years, Hebner has worked aboard research vessels, conducted graduate research on the vertical migration potential of deep-sea snail babies, and even dove to the bottom of the sea in Alvin, the famed research submarine that revolutionized deep-sea science. For Hebner, the world of scientific inquiry, data, and field and lab work, has increasingly felt like home.

But the world of marine policy was foreign to him—until recently. Now, as a fellow in the John A. Knauss Marine Policy Fellowship Program, Hebner is learning the ins and outs of policy decisions that impact the deep-sea realms he studies and explores.

The Knauss fellowship matches exceptionally qualified graduate students interested in ocean and coastal resources with year-long positions in executive and legislative offices of the federal government. Selected as a Knauss finalist in 2022, Hebner began his placement with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in February of this year.

"[The fellowship] gives graduate students a chance to do something they may not have otherwise had the chance to do by exposing them to the federal sector," Hebner said. "It really aligned with my goals to try something new, learn something different, and see if it's what I want to do."

Deep-sea beginnings and larval research

For his fellowship, Hebner was placed in NOAA’s Office of Ocean Exploration, a fitting spot for someone so passionate about the unexplored depths of the sea.

Originally from Albuquerque, New Mexico, Hebner’s interest in ocean exploration and marine science began with nature documentaries on TV, which eventually led him to pursue an undergraduate degree in marine biology at the University of Oregon. After graduating, he joined several research cruises to study deep sea ecology in the Gulf of Mexico.

On the first of those cruises, aboard the research vessel RV Atlantis in the Gulf of Mexico, he met Associate Professor of Biology Shawn Arellano, a WWU scientist specializing in the lives and behavior of nearshore and deep-sea larvae. During the cruise, Arellano was scheduled to make a dive in Alvin, the submarine that’s been enabling scientists to study the deep sea for decades—and Hebner was the lucky observing scientist chosen to accompany her.

Along with Alvin’s pilot, Drew Bewley of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Hebner and Arellano dived to a depth of 550 meters, recording encounters with fan corals, enormous, waving "bushes" of tubeworms, and slender, mirror-like fish that drifted past the submarine’s portholes over the course of their eight-hour dive.

"That was probably the single greatest moment of my life to date," Hebner said. "[The pilot] even let Shawn and me drive the sub around on the bottom of the ocean for a bit."

Motivated by his experiences at sea, Hebner enrolled at Western and began to work in Arellano’s lab as a graduate student, where he began to study the migration potential of snail larvae that live in cold seeps, extreme environments on the seafloor that leak oil and methane.

There’s actually very little that’s known about these deep-sea creatures, Hebner said. His research will pave the way for future studies by filling existing knowledge gaps.

"That was probably the single greatest moment of my life to date," Hebner said. "[The pilot] even let Shawn and me drive the sub around on the bottom of the ocean for a bit."

Mitch Hebner,

on his time aboard the Alvin submarine with Arellano.

Exploring marine policy with the Knauss fellowship

Hebner’s interest in policy stems from his desire to preserve the ocean environments he studies.

"If I could be involved in a small way to conserve, preserve and ensure the future prosperity of our national marine resources, that's something that I really wanted to be a part of," Hebner said.

A previous Knauss fellow herself, it was Arellano who encouraged Hebner to consider the fellowship. Through their collaboration in the field and lab, she recognized qualities she thought might allow Hebner to excel in the public sphere.

"Mitch is very responsive, and he works really well with other people. He had also gotten very interested in how you can represent data in ways that other people can easily consume," Arellano said, which is an important skill for science communicators.

For Arellano, the Knauss fellowship helped her understand how the research she was doing within academic institutions translated into action outside academia, as well as how government funding actually works, which is crucial for most scientific research.

Now several months into the fellowship, Hebner is learning how governments and other stakeholders work together: Part of his job is working with the National Oceanographic Partnership Program (NOPP), which coordinates between government, academic institutions, private organizations and philanthropy on projects to advance marine science and education.

He’s also part of two interagency working groups, including the National Ocean Mapping, Exploration, and Characterization strategy (NOMEC), which is tasked with mapping unexplored areas off the coastlines of U.S. borders and territories.

Hebner said his work in Washington is challenging, likening the steady stream of new information to drinking from a firehose. But it’s also been rewarding.

"It's entirely brand new. I'm definitely an academic scientist by background, and I’ve spent the majority of my career reading and writing papers, doing experiments, and learning about various critters," Hebner said. "But it's been a lot of fun, a huge learning experience, and a huge growth opportunity."

For Arellano’s part, working with students like Hebner who are discovering and refining their professional passions and interests is one of the best parts of the job.

"It’s wonderful. It’s exactly the reason I’m at Western," Arellano said. "Many of our master’s students come here not knowing exactly what they want to do, and it’s really fun to help them figure that out."