DDT Detective

They went searching on a hunch, a theory fed by decades of rumors.

And in the pitch-black darkness on that day in 2011, the rumors became fact. Almost 3,000 feet below the surface of the ocean on the floor of the San Pedro Basin between Los Angeles and Catalina Island, littering the seafloor, they found what they were looking for.

First they saw one barrel, and then another. Eventually dozens of them, all packed with industrial waste laden with DDT, one of the most toxic poisons ever created by mankind, a pesticide so genetically and environmentally harmful that it inspired the publication of Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring” in 1962 and almost single handedly gave birth to the modern environmental movement.

In 2013, Western Washington University Assistant Professor of Chemistry Karin Lemkau was there when they revisited this site. Lemkau, then a postdoctoral researcher with Professor David Valentine at UC Santa Barbara, remembered watching the barrels loom out of the inky darkness like traffic signs on a deserted highway.

"That far down, it’s so dark and quiet, and everything feels like slow motion. It really takes some getting used to," Lemkau said.

The research team had just finished sampling along a transect of hydrocarbon seeps – cracks in the earth’s crust where natural gas and oil percolate into the ocean, producing a unique ecosystem of bacteria, plants and animals. They had a few hours left to kill with their “rental” of Jason, the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) operated by scientists from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and they used them to revisit the dump site to further explore the thousands of barrels of DDT waste they had seen glimpses of in 2011.

“As many as 2,000 to 3,000 barrels a month were estimated to have been dumped there between 1947 to 1961. Where exactly were they? What condition were they in? And more broadly and importantly, what impact were they having? That’s what we wanted to find out,” she said.

Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane

It’s easy to see why scientists came up with an easy acronym for DDT: “Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane” does not exactly roll off the tongue. DDT was first synthesized in the 1890s and became heavily used during World War II to kill the mosquitos giving GIs in the Pacific tropical illnesses like malaria, typhus, and dengue. Hailed as a “wonder chemical,” it became available to the public as a household pesticide, although even then there were concerns over its use.

These concerns were raised dramatically by Carson’s book, which was critical of the broad use of DDT given its known deadly toll on other species, especially birds. One of the compound’s most insidious effects is known as bioaccumulation, or the ability to concentrate in greater amounts as it works its way up the food chain.

For example, DDT ingested by tiny animals such as zooplankton is magnified and stored in the fat of larger and larger creatures until reaching apex predators such as raptors, causing these birds’ eggs to thin dramatically and break. Bald eagles, peregrine falcons, and brown pelicans were all brought to the brink of extinction in the contiguous United States because of DDT. Links to cancer clusters in U.S. residents were also traced to DDT hotspots.

Wayne Landis, director of the Huxley College of the Environment’s Institute for Environmental Toxicology, has spent his career analyzing the impacts of pollutants, pesticides, and harmful industrial waste on the environment and the people who live in it, and he said DDT’s deadly environmental legacy in this country continues to unfold.

“DDT is the gift that keeps on giving,” he said. “Its use contributes to contamination decades after its manufacture was outlawed in the United States, and it is incredibly hard to dispose of.”

DDT was banned by the Environmental Protection Agency in 1972, and worldwide for almost all use in 2004 by the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants. India is the only nation left that still uses DDT in large amounts.

By the time Lemkau was viewing those barrels on the sea floor, the factory that made them had been long shuttered. But what damage had been done?

“The Solution to Pollution is Dilution?”

Lemkau said that the answer to many disposal problems after the war was simple: Dump it in the ocean.

“There was the notion that the ocean was so vast, that it could dilute anything you put into it without consequence,” she said. “That is just not true. It was a cheap way of avoiding issues of contamination.”

As barrel after barrel were discovered by the cameras of ROV Jason the previously collected sonar images came to life as did historical accounts of the disposal processes.

Some barrels were mere shells, others whole. Some showed punctures consistent with the anecdotal reports of barrels being intentionally ruptured prior to dumping to ensure they would sink.

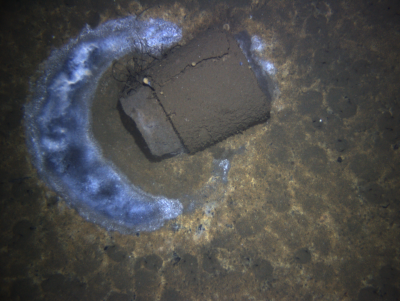

Many barrels showed distinct patterns in the sediments on the surrounding seafloor. Seemingly undisturbed sediments around the barrels had formed dense microbial communities. These “microbial rings” surrounding many of the barrels looked like white spray paint marking the extent of environmental contamination.

Lemkau and her colleagues used ROV Jason to gather dozens of sediment cores at a number of barrel sites, analyzing the sediment extracts via gas chromatography and mass spectrometry to better understand its composition.

This discovery is a warning. The ocean cannot be our dumping ground without environmental consequences. We can’t let this happen again.

“We found shockingly high concentrations of DDT. It wasn’t uniform – some samples had more than others. This makes sense for environmental samples in general, especially for hydrophobic compounds, such as DDT, which prefer to associate with particles rather than dissolve into the water. All samples taken near barrels showed elevated DDT concentrations, but more surprising was that some of the highest concentrations were not located near any visible barrels. Clearly the disposal process of these wastes was sloppy and decades later we are now getting a more accurate picture of how sloppy it really was,” she said.

“What we didn’t know, and what we are still investigating 10 years later, is how these levels of toxin impact the microbial life of the sea floor and what happens when an environment is exposed to these levels for this amount of time,” she said.

DDT has been found in measurable levels in many of the area’s fish for years; the Southern California commercial jack mackerel fishery was shut down briefly in the late ‘60s because DDT levels double the FDA’s minimum were the norm. Signs were posted at local piers that remain up today warning fishers not to keep or eat any fish with tumors (caused by DDT), and high levels of DDT remain in seals, sea lions, and other local marine mammals.

“DDT just doesn’t go away,” said Lemkau. “It’s an extremely tough, long-lived compound.”

Montrose, the company in Los Angeles that was the world’s largest maker of DDT and producer of a portion of the waste barrels discovered by Lemkau and her team, had also been dumping DDT-laced industrial waste straight into the city’s sewers. Via an outfall just offshore, this waste was distributed onto the shallows of the Palos Verdes Shelf, creating a Superfund site that would go down in history as the world’s largest concentration of DDT and result in more than $140 million in fines.

To illustrate how potent the levels were at some of the barrel sites, data has shown some of the collected barrel core samples to have levels 40 times higher than those from the Palos Verdes Shelf Superfund site. Moreover, while a small number of the barrels have been found, by most estimates half a MILLION barrels were dumped in the area, or even “short dumped” nearer to shore by employees who couldn’t be bothered to make it to the middle of the channel. The level of human-caused environmental catastrophe was staggering.

Endgame

Lemkau and every ecologist, toxicologist, and researcher that followed their initial discovery were greeted with one very difficult reality: cleaning this up would be incredibly complicated.

Removing the barrels and impacted sediments from the ocean floor isn’t a practical option as it would likely further spread the contamination rather than remedy the issue,” she said.

After the initial discovery state and federal agencies did some monitoring work of the barrels but that effort faded as newer crises emerged; the bottom of the ocean is easy to forget. But a recent Los Angeles Times project dredged up the story of these 500,000 barrels once again, and Lemkau said she hoped the new spotlight would result in renewed resolve to handle contaminants responsibly.

“This discovery is a warning. The ocean cannot be our dumping ground without environmental consequences. We can’t let this happen again,” she said.

“The story hasn’t changed. It comes in and out of focus as it gains and loses attention, but like DDT, it’s not going away.”

Karin Lemkau is an assistant professor of Chemistry at Western and a core faculty member in the university’s Marine and Coastal Science (MACS) program. She left UCSB in 2016 for her first academic position in the Corning School of Ocean Studies at the Maine Maritime Academy, and began her current position at Western in 2020. Besides the organic and analytical chemistry classes she teaches in her department, she also teaches oceanography, helping to train the next generation of ocean stewards and environmental detectives. She is looking forward to getting her research lab going here at Western where she will help graduate and undergraduate students explore and better understand the impact of humans on our coastal environment.